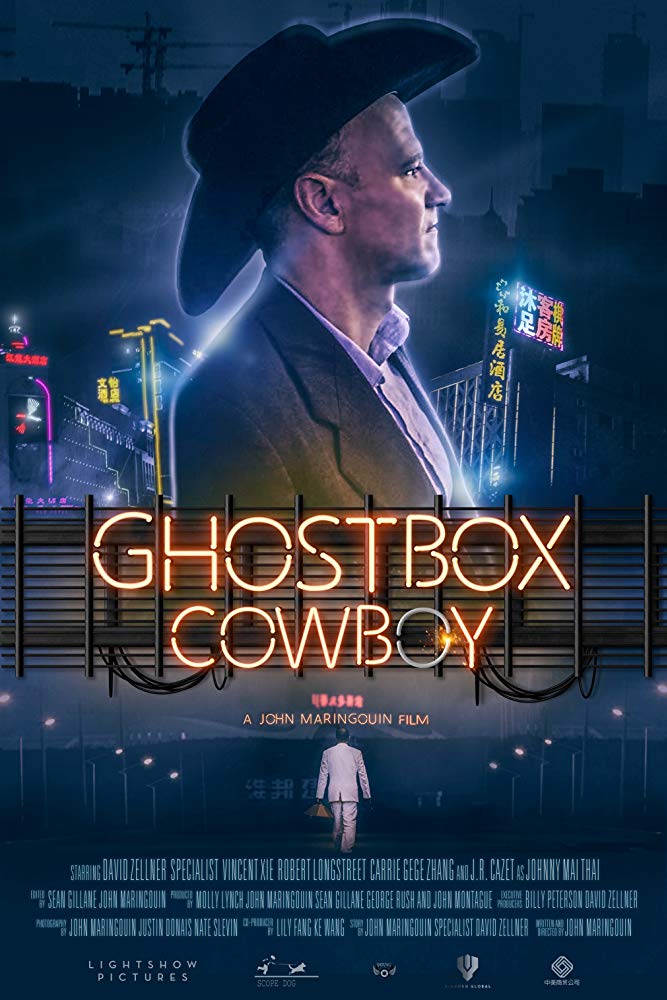

PIONEER MEDIA’S CHINA MANAGER DR. JOHN MCGOVERN REMINISCES ABOUT LOCATING LIVE CAMELS FOR GHOSTBOX COWBOY’S FEATURE FILM SHOOT IN THE CHINESE GHOST CITY OF ORDOS

“I need a camel and a camel herder.”

Sitting at breakfast in the hotel with a cup of coffee in hand the director John Maringouin smiled at me over the table after putting forward the first of many unusual requests.

“Don’t worry, you’re more than just providing location and translation services, you’re a proper fixer now!”

“Not a problem mate, I’ll find you your camel.”

We had been filming for a few days already for Maringouin’s indie film Ghostbox Cowboy. Maringouin as director, one actor in the extremely talented David Zellner, one camera operator in Saturday Night Live’s Nate Slevin, and a whole host of extras and myriad random ideas formulating themselves into shots as the days progressed. Guerrilla filming, as this style of filmmaking is called, which was an idea to which I was very much attracted.

I got on the phone and from my local contacts got the best idea of where to find a camel and a camel herder, in the best possible location for us. Located

in the Ejin Horo banner just adjacent to Kangbashi new district of Ordos city, we needed to head to the huge sand dune that overlooks the entire district.

“This whole area used to be grassland like you see out of town or dunes like this” explained Yang, my local driver.

“Do you think we’ll find a camel herder?”

“Yeah, there’s a guy who lives in a tent here and has a few camels!”

The sand dune here stands south of the huge reservoir and just north of a residential block eerily representative of the ghost city moniker of Ordos itself. The block looms empty and unfulfilled, a 20-storey tower of darkness on the edge of the Ordos grassland waiting for people to arrive.

And indeed, we found the camel herder’s tent, empty as everything else around here. After climbing half way up the dune though we spotted the camels in the distance and headed back down and into the scrub.

“We don’t eat camels here”, Yang explained matter-of-factly, “they grieve for their lost ones just like us.”

The camel herder himself was standing as you’d expect, leaning on his stick and wrapped in his thick army coat that would be vital for the harsh winter here.

“Hello comrade, can we borrow a camel?”

“If it will go with you, of course.”

I thought for a few moments about how we would lead a camel up to the dune, surveyed the height of it and the suspicious look on its face, and started again.

“How much would it be to borrow a camel?”

“100 yuan.”

“How long can we keep it?”

“As long as you want.”

We had secured the camel.

Now I had to try to encourage the herder himself to join the cast of the film, as Maringouin wanted to shoot footage of our main actor swapping his product – ghostboxes – for a camel so he can trek out of the desert.

“Comrade, would you mind us recording you passing over the camel and receiving the ghostboxes in return for the film we’re making?”

“Go ahead, no problem.”

“The film is about –”

“I don’t care, I don’t watch films, but you can do whatever you want to do!”

He never even questioned what a ghostbox was! But he acted the part, looking over the ghostbox and pretending this was a viable swap for a camel, before handing over the camel’s reins to our actor and walking up the first dune together.

He stood and watched over our actor’s scenes of madness in the desert with the camel as though this was all in a day’s work for him, or as though it’s not that weird at all that a guy with just a camel and some ghostboxes would go mad in the desert.

Over dinner as we raised our glasses Maringouin said, “this one’s for the camel and the camel herder!”

All in a day’s work… Ghostbox Cowboy went on to premiere at the 2017 Tribeca Film Festival, and was lauded as a “gonzo odyssey” by the Hollywood Reporter.